Is this how Israel can stop the next hostage crisis before it begins?

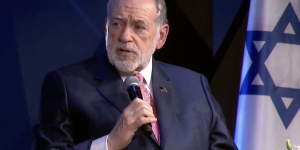

Knesset Member Ohad Tal has submitted legislation aimed at preventing the next kidnapping of an Israeli citizen before it happens. The bill, which is currently before the Ministerial Committee on Legislation, seeks to remove the incentive for terrorist groups to capture Israelis, Tal said.

In explaining the rationale behind the proposal, Tal argued that Israel’s past policies have unintentionally encouraged kidnappings.

“The truth is uncomfortable but unavoidable: over the years, Israel has created a built-in incentive for the kidnapping of Israelis, turning it into one of the most effective weapons in the hands of our enemies,” Tal, a member of the Religious Zionism party, wrote in an opinion piece in The Times of Israel.

Speaking to ALL ISRAEL NEWS, Tal stressed that the current moment presents a rare opportunity to act. With no Israelis currently held captive, he said, now is the time to pass a law that “removes kidnapping as a strategic weapon from our enemies’ hands.”

For the first 40 years of the State of Israel, the government maintained a policy of not negotiating with terrorists. Instead, rescue missions became part of Israeli national lore. One of the most famous was Operation Entebbe in 1976, when Israeli special forces stormed the tarmac in Uganda and rescued 102 hostages from an Air France plane hijacked by Palestinian and German terrorists.

That approach was also evident two years earlier, in 1974, when members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine took more than 100 hostages at a high school in Ma'alot. Rather than negotiate, Israel launched a rescue operation with elite IDF forces. The mission failed, and 25 hostages, including children, were killed, with dozens more injured.

An earlier case occurred in 1972, when Black September terrorists hijacked Sabena Flight 571 from Vienna to Tel Aviv. While pretending to negotiate, IDF commandos launched a surprise operation. Disguised as technicians, they boarded the plane after it landed at Lod Airport, killed two terrorists, and arrested two others. All of the passengers were rescued except for one woman, who later died of her injuries.

According to Tal, Israel’s longstanding refusal to negotiate reflected an understanding that talks with terrorists carry a steep cost. He told ALL ISRAEL NEWS that negotiating with terrorists grants them legitimacy, and the country often pays a price so high that it encourages future kidnappings.

“We cannot send these messages or pay these heavy prices,” Tal said.

He added that today, a terrorist knows he will pay a lesser price for kidnapping an Israeli than for stealing a car or committing many other crimes. As a result, terrorists learn that they do not need missiles or state-of-the-art aircraft to strike Israel. Instead, he said, “they just kidnap one Israeli and take this country down to its knees.”

The policy of not negotiating with terrorists began shifting in 1979, following the kidnapping of soldier Avraham Amram. In that case, Israel carried out its first prisoner exchange, releasing 76 Arab terrorist prisoners in return for the soldier, who had been captured in Lebanon.

More than three decades later, in 2011, Israel concluded what many consider its most infamous deal. The government exchanged more than 1,000 Palestinian terrorists held in Israeli prisons for IDF soldier Gilad Shalit, who had been held hostage in Gaza. Among those released was Yahya Sinwar, the mastermind behind the October 7th Hamas massacre that killed 1,200 Israelis and led to the kidnapping of 251 others.

As Tal wrote in his Times of Israel article, “This was not an unforeseeable tragedy; it was the direct result of policy.”

In the aftermath of the Second Lebanon War, the Winograd Commission called on Israel to embrace a comprehensive strategy on kidnappings. In 2008, a committee led by former Supreme Court Justice Meir Shamgar was established to address the issue. The Shamgar Committee released its conclusions in 2012, after the Shalit deal.

According to Tal, however, the guiding principle was clear: a country like Israel cannot decide how to handle a kidnapping in the midst of a crisis. Instead, policies must be set in advance and upheld even under intense pressure.

Tal is now seeking to revisit the Shamgar framework and has submitted legislation based on its principles for discussion in the Knesset. The bill places limits on the price Israel may pay if it decides to pursue a deal. It requires that, before any negotiations or agreement, an international organization be designated to visit the hostages, assess their condition, and guarantee they receive necessary care.

Under the proposal, Israel would not release more than one terrorist per hostage. Any terrorist released would have to have served at least two-thirds of their sentence. Palestinian Israelis would not be eligible for release. The bill also includes provisions barring the release of terrorists convicted of certain degrees of murder.

“The price will be limited,” Tal told ALL ISRAEL NEWS.

From Tal’s perspective, the legislation itself is not the main point. Rather, the goal is to force a national discussion and reach conclusions that “best serve the security of the State of Israel.”

“The most important thing is that we will now sit together and discuss what limitations we want to put on ourselves,” Tal said. “The purpose of the bill is to facilitate a discussion, come up with conclusions and then legislate them.”

Tal emphasized that the effort should not be viewed through a right-wing or left-wing lens. He noted that many leaders on the left had previously sought to legislate the Shamgar principles into law, but ultimately refrained. According to Tal, it was human pain, not a lack of principle, that prevented those efforts from moving forward.

He added that the responsibility of elected officials goes beyond returning hostages who have already been kidnapped. It also includes lessening the likelihood of kidnappings in the first place.

“When we send soldiers to operations, they risk their lives, and sometimes they fall. This is the price we pay, and because soldiers die, it does not mean that we cancel the army,” Tal concluded. “We need to do whatever we can to protect ourselves, and a clear policy on hostage negotiations protects the whole society.”

.jpg)

Maayan Hoffman is a veteran American-Israeli journalist. She is the Executive Editor of ILTV News and formerly served as News Editor and Deputy CEO of The Jerusalem Post, where she launched the paper’s Christian World portal. She is also a correspondent for The Media Line and host of the Hadassah on Call podcast.