From Hebrew to Hebrew: How the Bible got a new language in Israel

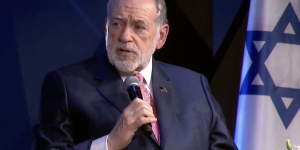

Bridging the gap: Modernizing the Hebrew Bible's ancient text for today’s Israeli readers – An interview with Yair Frank, the project leader

What does it mean to "understand" the Bible in Israel today? The Bible Society in Israel has worked for five years to make the text of the Hebrew Bible speak in modern Hebrew – without losing its meaning, its layering, or its cultural weight.

We spoke with Yair Frank, the project leader, about where the line lies between translation and interpretation, why the new text did not end up as "street language," and why this edition could be crucial even for those who haven’t opened the Bible since their high school final exams.

Interview by Judit Kónya, Izraelinfo:

Could you introduce yourself in a few words? What do you do?

I have been working at the Bible Society in Israel for over eleven years; currently, I manage the Society's larger projects. For the past five years, our most important work has been the modernization of the Hebrew Bible – that is, transplanting the text into today's modern Hebrew language.

Previously, I led the revision of the Hebrew translation of the New Testament. That is a completely different field: there, we had to translate ancient Koine Greek text into Hebrew. In summary, I manage all projects at the Society that are directly related to the text of the Bible.

My professional background: I studied Tanakh – at is, the Hebrew Bible – and the History of the Jewish People at the Hebrew University.

In the name of the Bible Society, does "kitvei ha-kodesh" – "holy scriptures" – refer to the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament together?

Yes. The Bible Society in Israel was established in 1948, the year the state was founded. Before the establishment of the State of Israel, during the British Mandate, the British and Foreign Bible Society operated an office here, which became an independent, local society in parallel with the founding of the state.

Which religion or church is the organization affiliated with?

Just as in other countries around the world, the Bible Society in Israel is not tied to any single church or denomination. The Society's goal is to disseminate the Bible, meaning to make the biblical text accessible to everyone regardless of linguistic, cultural, or religious background.

At the same time, the historical background is clearly rooted in Christianity: the international movement of Bible Societies originated from that sphere. We make the Bible – both the Old and New Testaments – equally available.

The staff of today's Bible Society in Israel are local Jews, the majority of whom are Messianic Jews. Accordingly, we accept both the Old Testament and the New Testament as holy scripture.

There are Bible Societies in most countries of the world, but where is the "head" of the organization? Who coordinates the operations of the local societies?

There is no "head." One of the most interesting features of the system is that it is not built hierarchically, but operates like a network. For example, I know some staff members of the organization in Hungary, I know who works there, but beyond that, there is no institutional connection between us. Every local society is completely autonomous and independent, makes its own decisions, and operates with its own responsibility.

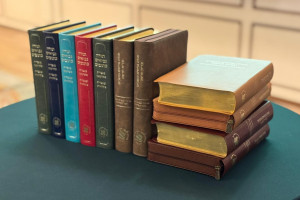

This year, in December 2025, the Bible Society in Israel published the text of the Bible transposed into modern Hebrew. This is a "bilingual" edition, correct?

Not exactly. The volume is monolingual, but it contains two texts. The Masoretic text based on the Leningrad Codex appears in one column, and on the same page, the version transposed into modern Hebrew can be read.

So, the text of the Hebrew Bible and its modernized version stand side by side – meaning you translated the Hebrew Bible into Hebrew.

Actually, this is not a classic translation, but an intra-lingual modernization.

Who worked on the project?

At least twelve people participated in the work with varying degrees of intensity.

Are they all Israelis and Messianic believers?

Not everyone. For instance, the linguistic editor of the modern Hebrew text is not a Messianic believer: he is an atheist Jew who also works with the Academy of the Hebrew Language (*HaAkademia LaLashon HaIvrit*), and he participated in this project with great joy.

Can the contributors be named?

A decision was made within the Bible Society that the names of the contributors would not appear in the publication. The book contains neither my name nor anyone else's – only the text. If this decision changes, the names may be published later. My role is known regardless of this.

What was your specific task?

Coordinating the work of the entire team. In the first phase of the work, we transposed the biblical text into modern Hebrew. This was followed by a second, research phase: we examined the finished text verse by verse and checked, using philological tools, how faithful the modernized version was to the original meaning, and to what extent the translators followed the source text.

I participated actively in this phase myself.

Did the translators have linguistic competence to interpret Greek, Latin, and other Bible translations?

The translators are professional translators who have been working in the profession for twenty to thirty years. They translate from other languages into Hebrew; Hebrew is their mother tongue. Furthermore, they have all read the biblical Hebrew text for many years, know it well, and use it on a daily basis.

So they do not have a background in biblical studies.

No. Biblical studies is not their field of expertise.

But they know biblical Hebrew deeply.

Yes. They grew up on it, they read it, and they use it every day.

Is that why the second phase was necessary?

Exactly. That is why it was important that in the second phase of the work, experts who are researchers in various fields of biblical studies worked on the text. They went through the translated text verse by verse, and where the translators misunderstood the text, they corrected the translation.

Every translation is actually an interpretation, and here it is worth discussing the Christian background of the project again. Interpreting the text of the Bible is a theologian's task. To what extent do you consider this modernized text to be theologically thought-out?

Indeed, every translation is interpretation. Therefore, one of the basic principles of the project was to approach the text with the greatest possible philological fidelity. We consciously had no prior theological goal or direction that would have influenced the translation.

We performed philological work: we tried to reproduce the meaning of the text accurately in modern Hebrew without "conveying" any theological message. We paid special attention to this during the work.

I looked at a few biblical passages on the Bible Society's website – for example, the psalm beginning "By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept..." [Ps. 137:1], and the Song of Songs – and I see that the changes are primarily lexical. You intervened in the text where a Hebrew word is now unintelligible or its meaning has changed over time. For example, in the modernized version of the cited psalm, they do not hang a "kinor" [Heb., in modern sense: "violin"] on the willow tree, but a lyre [Heb. lira]. Was this the goal?

Yes. It was a fundamental criterion for us to preserve the original meaning of the biblical text while making it accessible in modern Hebrew. To do this, we often had to swap words, but the sentence structure also differs fundamentally in biblical Hebrew, so we had to change almost every sentence. If the meaning of a word has become obscured or changed by today, we had to use a different expression so that the reader truly understands what the text originally meant.

Like in the case of "kinor," the meaning of which has changed in the meantime.

Yes.

I found another interesting example in the Song of Songs [Song of Songs 1:5]: the tent cloth [Heb. yeriot] of Solomon's tents appears as curtains – vilonot – in the modernized text. What justified this solution? The word yeriot is indeed difficult to understand today, but how did you arrive at the interpretation of vilonot?

We strove to find the most accepted interpretation of rare words – or even hapax legomena, expressions that occur only once in the Bible – one that the majority of biblical scholars also accept.

In this case, based on the historical context, the text refers more to the interior spaces and curtains of Solomon's palace, not to tent cloths. That is why we chose the term vilonot.

Here, the role of Greek, Latin, and other translations comes in as well. But then, is the source text for the modernization not only the Hebrew Bible but also these translations?

No, because it was a fundamental stipulation for us that the source text be exclusively the Leningrad Codex.

At the same time, other translations and commentaries are still needed to interpret the text, aren't they?

Of course, but this [the Codex] was the base, with all its faults. The Leningrad Codex does have clear textual problems.

Are you referring to errors stemming from text copying?

Yes. We translated these errors as well, but where it was clearly visible that the text was damaged or problematic, we indicated in a footnote, for example, that "the Septuagint translates it this way," or we indicated other text variants, such as the different readings of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

However, the translation itself is consistently based on the text of the Leningrad Codex.

What provided the most work: the lexical, syntactic, or stylistic changes?

All of them, but perhaps the lexical questions took up the most time. We worked for long months, even years, to find the right words. Additionally, however, the text had to be stylized. When the modernized Hebrew version was completed, it was an important criterion that it should not sound like street language, but rather high-level, literary Hebrew.

For example, you kept the word hinne [Heb. "behold"].

Yes. You can feel that you are reading a carefully formulated, understandable text that also has literary value.

What kind of reader did you imagine?

We didn't think of a single, well-defined reader. The goal was for the text to be understandable to as many readers as possible. To readers for whom Hebrew is their mother tongue and who have finished elementary school – so that even a teenager could understand the text.

Israeli society is extremely complex, with many new immigrants whose Hebrew language skills are not necessarily at a high level. We knew that for them, this text might still pose a challenge because we placed the linguistic standard above their level. We tried to set this standard so that the text reaches as many people as possible, while also being aware that it is impossible to speak to everyone at once.

So you are providing a text of literary value that is nonetheless accessible. Where is the modernized Bible available? Are you distributing it in book form as well?

The printed volumes arrived from the press about a week or a week and a half ago. The text is also available online, and the book can be purchased at the Bible Society's three local bookstores – in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem.

In addition, we are already working on getting the edition to major book distributors as well.

So there is an intention for the text to be physically present before people.

Definitely. The goal is for it to become common knowledge in Israeli society: a modernized text exists.

Have there been reactions to the text yet?

Yes, there is feedback, and so far it is specifically enthusiastic. Those who have a principled problem with us touching the text of the Bible won't pick up the book in the first place.

It is quite certain that there will be negative reactions as well. At the same time, it is important to see that we did not invent the idea of modernizing the Hebrew Bible. The necessity of this work is self-evident, as the Bible is a collection of books that are more than two thousand years old.

Already in the early 2000s, a similar initiative was born: the Yediot Aharonot publishing house launched the Tanakh Ram project (תנ”ך רם), in which they transposed the Torah and the Early Prophets into modern Hebrew. However, the work was left unfinished, partly due to professional criticism. The translation was the work of a Bible teacher, but professionally it did not stand up to scrutiny.

They also started from the premise that there is a need to modernize the biblical Hebrew text.

They reached a point – the narrative books are relatively easier to transpose – but the truly difficult parts are the prophetic books, wisdom literature, and similar texts.

Has your relationship with the Bible changed during these five years? Am I right to think that dealing with the text took up most of your workday?

Absolutely. I grew up on the Bible and it is no coincidence that I studied this at university as well. I taught Bible and history for a few years, but when I embarked on this project, from then on, I literally woke up and went to bed with it. Day in and day out, I dealt only with the text. One learns an enormous amount this way; newer and newer layers of the text are revealed.

You now know the Bible as few do.

Yes, that is true.

Was your connection to it not as close before, or am I mistaken?

My connection was always very close. I read it continuously, I dealt with the text constantly. I moved to Israel at the age of sixteen, learned Hebrew, and barely a year later I already had to take my matriculation exam (*Bagrut*) in Tanakh. It was then that I decided I would no longer read the Bible in Hungarian. I already knew the Hungarian translation well, but I was increasingly interested in what was in the original text. From then on, I dealt with this continuously; I know and love the text. In this sense, my relationship hasn't changed, only deepened: for the past five years, I have dealt with this eight hours a day.

Is distribution also your task, meaning does it also depend on you how this text – on which twelve people worked for five years – reaches as many readers as possible? This is a work of huge volume.

This is not a one-person task, but the work of the entire Bible Society. Naturally, I have influence on how we do it, but the whole thing does not rest on my shoulders.

With what feeling would you go to your university professors with this volume? What would you say to them?

Just earlier this week I was at the Hebrew University, and I went in to see one of my former lecturers. I gave him the book, told him I worked on it – and he even asked for a dedication.

He was very curious; we leafed through the book and looked at a few specific translation decisions, precisely in the topic he was writing an article about at the time. The initial reaction was specifically positive.

At the same time, I am sure there will be critical feedback as well. I await with curiosity how academic circles will react and whether they will point out places where they think it could have been translated better.

The text can always be revised.

So you are waiting for the criticism?

Of course. I welcome it. Let them show the errors, and if we indeed made mistakes, we will change them. The main thing is that the translation is finished and is laid on the table.

What is the most important thing for you in this project?

When the thought of modernizing the Hebrew Bible first arose within the Society, I was the only one who received it with reservations. Precisely because I love the text of the Bible very much: it is extremely layered, rich, and beautiful, and not all the treasures and subtleties of the original text can be fully preserved in a modernized version.

For a long time, I argued that perhaps there is no need for this. Then I realized that yes, there is. Because the vast majority of people do not understand the text on first reading and cannot enjoy reading it.

The Hebrew Bible is not just a religious text, but in a cultural sense, it is the foundational text, the charter of the Jewish people – the text upon which we stand as a people and as a nation. Zionism, which brought us back to this land and made the founding of the state possible, is also deeply rooted in the Bible. If this text is not accessible to modern Hebrew speakers, then there is a serious deficiency there that must be corrected.

We cannot expect people to invest years in mastering the biblical language just so they can read without problems the book upon which this entire culture is built. I taught Bible in high school, and I saw with my own eyes how difficult it is for modern Hebrew-speaking students – young and old alike – to interpret, or even simply enjoy, the text.

That was when I understood that I had to put aside my own reservations, and yes, the text must be transposed into modern Hebrew. Knowing as well that the Masoretic text is not disappearing: it stays here with us, anyone can learn it, can delve into it. But regardless, there is a need for an accessible, modern text of literary quality that faithfully returns the original meaning.

And since the original text, the Hebrew Bible, is also included in the edition, it is conceivable that some readers will encounter it for the first time in this very way.

In Israel, everyone takes matriculation exams in the Bible, but after the exams, most put it aside and never look at it again because a large part of the text is unintelligible to them.

They still get it in the army, right?

Yes. They receive it for the swearing-in ceremony.

But not so they actually read it.

No. Even though it is a beautiful, extremely rich text. Independent of questions of religion and faith, it is of enormous value in a cultural sense, one of the foundational works of Jewish culture, which everyone should read at least once. The modernized Hebrew Bible provides an opportunity for exactly this.

The interview was first published here and is republished with permission.

The text of the Contemporary Hebrew Bible is available on the website here.

You can purchase the Modern Hebrew Bible here.

You can purchase the Modern Hebrew Old Testament here.

One gift. One Bible. One life touched. For every $25 you give, we place a Bible like this into the hands of an Israeli.

Izraelinfo.com is a non-profit, independent online news magazine. It publishes original news related to Israel, thought-provoking, critical and sometimes controversial opinion articles and essays.

You might also like to read this: