How many people named Herod appear in the New Testament?

Most Christians are familiar with the horrific story of King Herod ordering the slaughter of the innocent infants in Bethlehem after learning from the Magi that a child had been born who was destined to be the King of the Jews (Matthew 2:1–12).

However, when reading the New Testament, the repeated appearance of the name “Herod” can be confusing. Who exactly is being referred to in each passage?

In fact, the New Testament speaks of three different individuals named Herod, all members of the same ruling family. This article seeks to bring clarity and order to these figures, while also highlighting extra-biblical historical evidence that supports the biblical accounts.

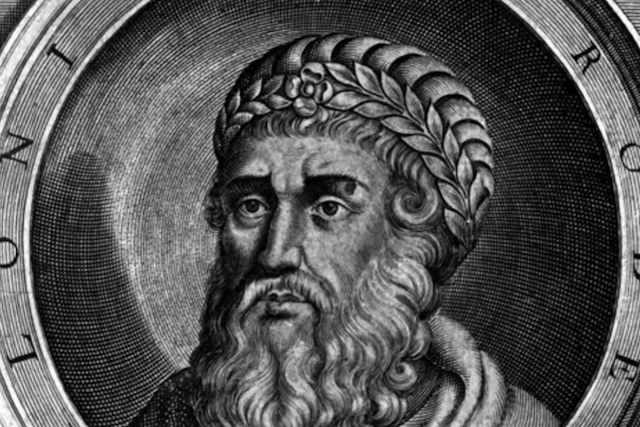

Herod the Great: The king at Jesus’ birth

The first and most infamous figure is Herod the Great, referred to by Matthew simply as “Herod the king” (Matthew 2:1). He appears in connection with the birth of Jesus and is also mentioned in Luke 1:5 as the ruler during the lifetime of Zechariah and Elizabeth, the parents of John the Baptist.

Although the massacre of the infants in Bethlehem is not recorded in non-biblical sources, it fits perfectly with Herod’s well-documented character. Herod was notorious for his paranoia and cruelty. As his reign progressed, his fear of rivals intensified, leading him to execute anyone he suspected of threatening his throne.

Tragically, this included members of his own family. He ordered the execution of his beloved wife, Mariamne the Hasmonean, as well as their two sons, Alexander and Aristobulus. Shortly before his own death, he even had his firstborn son, Antipater, put to death. A saying attributed to the philosopher Macrobius captures Herod’s reputation: “It is better to be Herod’s pig than his son.”

Herod also executed Jewish religious leaders and members of the Sanhedrin, making him deeply hated among the Jewish people. Against this backdrop, the Gospel account of the slaughter of Bethlehem’s infants is entirely consistent with his known behavior.

Herod the Great died in 4 BC, which raises an apparent chronological issue. If Jesus was born in the year 0 AD, how could Herod have attempted to kill Him?

This problem arises from a later miscalculation. The dating system known as Anno Domini was established in 525 AD by the monk Dionysius Exiguus, whose calculations are now widely regarded as inaccurate. Most modern scholars agree that Jesus was born between 6 and 4 BC, during the final years of Herod’s reign. When understood correctly, the Gospel timeline aligns well with known history.

Herod Antipas: The ruler during Jesus’ ministry

Whenever the Gospels mention “Herod” during the years of Jesus’ public ministry, they are referring to Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great.

After Herod the Great’s death, his kingdom was divided among three of his sons, Archelaus, Philip, and Herod Antipas, and his sister Salome I.

While Archelaus and Philip are named explicitly in the New Testament, Antipas is consistently referred to simply as “Herod.”

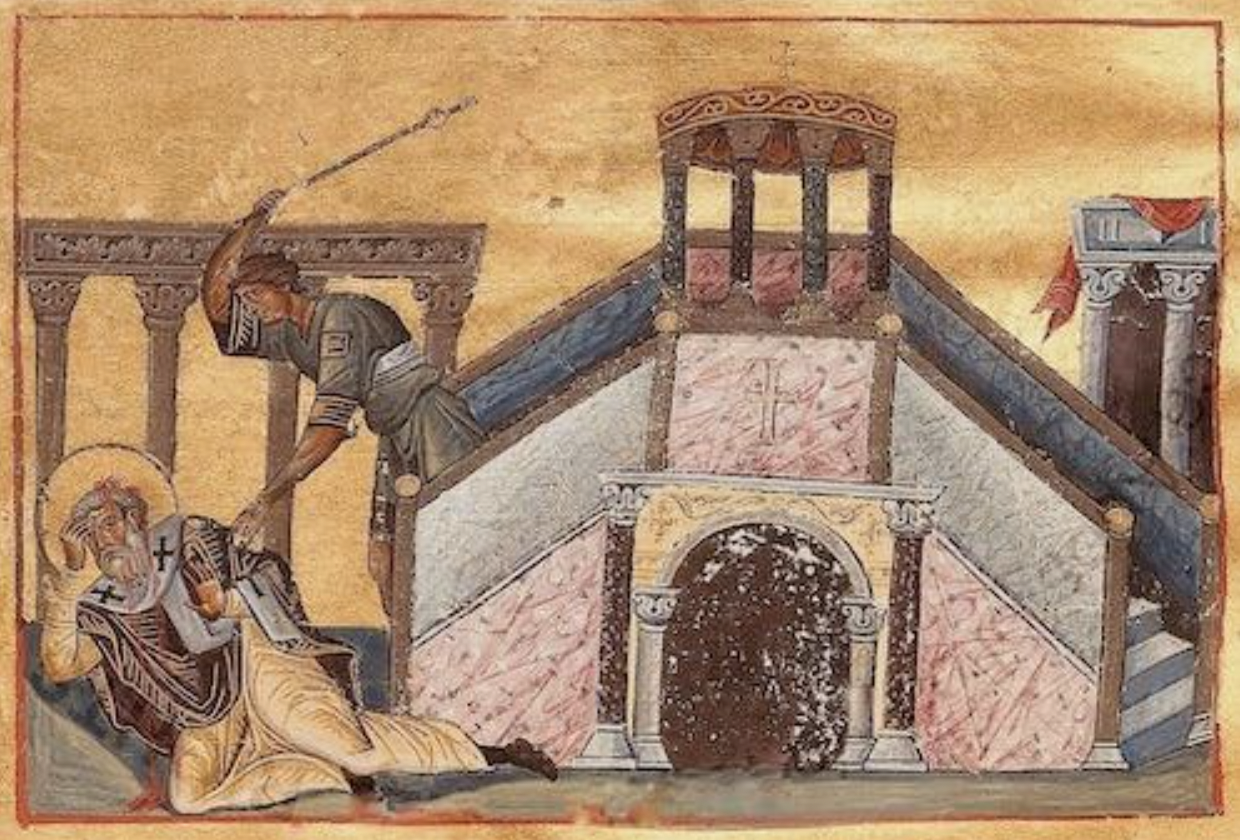

Herod Antipas is most infamous for his role in the death of John the Baptist. He unlawfully took Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, as his own. John publicly rebuked him for this sin, which led to John’s imprisonment.

Herodias harbored a deep hatred for John and waited for an opportunity to have him killed. That opportunity came during a banquet, when her daughter danced and pleased Herod Antipas so much that he promised to grant her any request. Prompted by her mother, the girl asked for John the Baptist’s head (Mark 6:14-29).

Agrippa I: The Herod of the Book of Acts

In the Book of Acts, the name Herod appears once again, but this time it refers to Agrippa I, the grandson of Herod the Great.

Agrippa was the son of Aristobulus, one of Herod the Great’s sons whom the king had executed. Through his grandmother Mariamne, Agrippa was a descendant of the Hasmonean dynasty. Thanks to strong political connections in Rome, Emperor Caligula appointed Agrippa as king over Judea, granting him authority similar to that once held by his grandfather.

Although known to historians as Agrippa I, the New Testament refers to him simply as Herod.

Agrippa I was popular among the Jewish people, yet he violently opposed the early Christian movement. Acts 12 records that he ordered the execution of James, Jesus’ brother, and imprisoned Peter.

His reign ended dramatically. After delivering a public address, Agrippa accepted the crowd’s praise that his voice was “the voice of a god, not of a man.” Immediately, an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he died, “eaten by worms” (Acts 12:20–25). This account is corroborated by the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, providing strong historical confirmation of the biblical narrative.

Conclusion: Three Herods, one historical reality

In addition to these three rulers, other members of the Herodian family appear in the New Testament, including Philip, Archelaus, Herodias, Salome, Agrippa II, and others. All are historically attested figures known from Josephus and other ancient sources.

In summary, the New Testament refers to three distinct individuals named Herod:

The father: Herod the Great – the king at Jesus’ birth

The son: Herod Antipas – the ruler during Jesus’ ministry

The grandson: Herod Agrippa I – the king who persecuted the early Church

Understanding these distinctions helps readers avoid confusion and deepens confidence in the historical reliability of scripture.

Ran Silberman is a certified tour guide in Israel, with a background of many years in the Israeli Hi-Tech industry. He loves to guide visitors who believe in the God of Israel and want to follow His footsteps in the Land of the Bible. Ran also loves to teach about Israeli nature that is spoken of in the Bible.

You might also like to read this: