Not yet, part II: Covenant confusion, Christ’s centrality, and the question of Israel

A dispensational, Scripture-first reply to Yochanan—from his arguments in the Comments Section

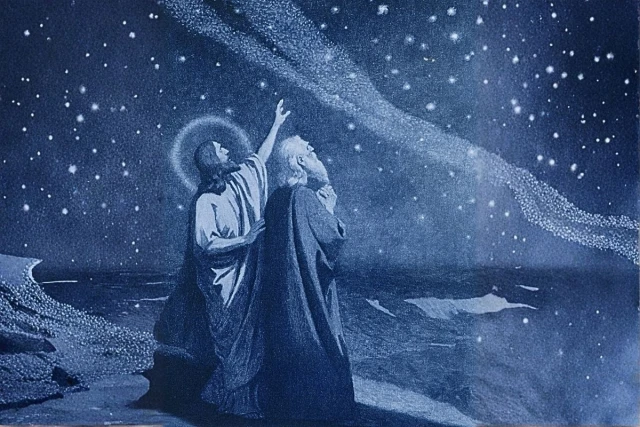

There is a moment in Genesis when night becomes a courtroom.

Abram has believed God. He has obeyed God. He has been rescued by God. And still he asks the question that honest faith asks when it stops performing and starts trembling: “O Lord GOD, how may I know that I shall possess it?” (Gen. 15:8).

God’s answer is not a slogan. It is a covenant-cutting.

Animals are divided. Blood is spilled. Darkness falls. Abram is put into a deep sleep. And then—this is the hinge—Abram does not walk through the pieces. God does. God passes alone between the parts, symbolized by the smoking firepot and flaming torch (Gen. 15:12, 17). That is covenant language: God binding Himself to His promise.

Dr. Thomas Constable summarizes the point bluntly: in covenant-making rites, two parties normally pass between the pieces, but “on this occasion… God alone passed between the parts,” indicating Abram had “no obligations to fulfill to receive the covenant promises.” See Constable’s Genesis 15 notes. For scholarly treatment of the Genesis 15 animal rite, see Gerhard Hasel’s Journal for the Study of the Old Testament article.

That is the fulcrum of the Israel debate—and it is the fulcrum Yochanan keeps stepping around.

Yochanan’s critique isn’t casual disagreement. It’s an indictment. He calls Christian Zionism “propaganda,” says Israel forfeited its covenantal claim, insists the prophets speak only to Babylon, declares the Bible “entirely silent” about any later regathering, and labels it “theological malpractice” to speak of any Israel-future while Hebrews says the Old Covenant is obsolete.

Because this line of argument is spreading—especially among younger evangelicals who rightly fear propaganda Christianity—it deserves a careful, Scripture-first reply: not with politics, but with covenants, context, and Christ.

Before we disagree, we should name what we agree on: salvation is one way for Jew and Gentile—through Messiah Jesus alone (Rom. 10:11–13). And no covenant grants moral impunity. Any theology that treats Palestinians as disposable, or baptizes violence as righteousness, is foreign to the prophets and foreign to Christ.

So the dispute is not whether Christ is central. He is. The dispute is whether Christ’s centrality cancels God’s oath-bound commitments—or crowns them.

The argument in one sentence

Yochanan’s system depends on one lever—Sinai’s conditionality—to cancel Abraham’s promise. But Paul explicitly forbids that move: “the law, which came 430 years afterward, does not annul a covenant previously ratified by God.” (Galatians 3:17 (ESV).) Sinai disciplines; it does not dissolve. Genesis 15 is God’s answer to the fear that human failure can make God unfaithful.

1) “Israel forfeited its covenantal claim because Sinai was conditional.”

This is the category error at the center of Yochanan’s critique: he treats Mosaic conditionality as if it nullifies Abrahamic oath. Yes, Sinai contains “if/then” structures and real curses. Yes, exile is covenant discipline. But that is precisely why Genesis 15 matters: the land promise is ratified by an oath in which God alone walks through the pieces.

Paul addresses this exact issue. He does not say “Sinai worked out Abraham, so Sinai can cancel Abraham.” He says the opposite: the promise came first, and the law cannot void it. See Galatians 3:17–18 (BibleGateway, ESV).

Yochanan also appeals to Jesus’ parable of the tenants: Israel were tenants, not owners, and they killed the heir. The warning is real—but notice what the parable assumes: the owner remains the owner. Judgment falls on wicked stewards; it does not convert the landlord into an oath-breaker. Paul makes the same point with different imagery: branches can be broken off “because of unbelief,” and the natural branches can be grafted in again (Rom. 11:20–24).

So yes: under Moses, Israel can be disciplined and scattered. But Israel’s sin cannot make God a liar—because God bound Himself by oath to Abraham.

2) “Restoration is conditional (Leviticus 26; Deuteronomy 30), so modern Israel can’t be any fulfillment.”

Yochanan is right that restoration texts include repentance and cleansing. But he draws the wrong conclusion: he treats the presence of conditions under Moses as proof that the Abrahamic grant is revocable. Moses himself refuses that logic. Deuteronomy warns of scattering “from one end of the earth to the other” (Deut. 28:64) and then speaks of regathering even from the “most distant land under the heavens” (Deut. 30:4).

Discipline and regathering coexist because Sinai does not overwrite Genesis 15; it presupposes it. The law can expel Israel from enjoyment; it cannot revoke God’s sworn grant.

The cleaner way to say it is this: Mosaic conditionality governs Israel’s enjoyment of blessing; it cannot cancel God’s title-grant sworn to Abraham.

3) “The prophets were only addressing Babylon; Ezra–Nehemiah fulfills them.”

True in part, false as a totalizing rule. The Babylonian return is real and recorded with confession. But Scripture’s regathering horizon is not reducible to one empire and one return. Isaiah speaks of gathering the dispersed “from the four corners of the earth” (Isa. 11:12) in an explicitly messianic passage (Isa. 11:1–10). The point is not that Isaiah “names 1948.” The point is that Scripture itself describes a horizon wider than Babylon.

That is why Paul, after the resurrection, still treats Israel’s story as unfinished—and warns Gentiles against boasting.

4) “A return before repentance—‘home in unbelief’—is a complete fabrication.”

The slogan can be abused. The sequence is not invented. Ezekiel depicts God’s initiative operating in stages: in Ezekiel 36, gathering precedes cleansing and Spirit-renewal (Ezek. 36:24–27). Ezekiel 37 intensifies that order: bones assemble, sinews and flesh appear, and only then does breath enter and the body stands alive. This is not a permission slip for unbelief; it is a warning that God can be faithful to His oath while the nation still needs eyes opened.

Zechariah adds a decisive detail: the inhabitants of Jerusalem are already there when God pours out “a spirit of grace and pleas for mercy,” and they mourn as they recognize the One they pierced (Zech. 12:10). The great turning happens in Jerusalem, not in Babylon.

So if “home in unbelief” offends our sensibilities, Scripture’s answer is: it should. It is sobering, not triumphalist. It is the sort of dangerous interval in which the church must preach the gospel, not canonize a state.

5) “Hebrews says the Old Covenant is obsolete—talking this way is theological malpractice.”

Hebrews does say the first covenant is “obsolete” (Hebrews 8:13 (ESV)). But notice what Hebrews does to make that point: it quotes Jeremiah 31, and Jeremiah’s New Covenant promise is explicitly “with the house of Israel and the house of Judah” (Jeremiah 31:31–34 (BibleGateway, ESV)).

Hebrews abolishes the Levitical system as a saving structure; it does not revoke God’s oath to Abraham. Invoking Hebrews to erase Israel is therefore self-defeating: Hebrews proves Sinai is surpassed, not that Abraham is revoked.

6) “Jewishness is not ethnic; covenant identity has always been spiritual.”

True for justification; false as an erasure of peoplehood in history. Paul rejects ethnic presumption (Rom. 2:28–29), and Revelation warns of false claimants (Rev. 2:9; 3:9). But Paul also speaks of “my kinsmen according to the flesh” (Rom. 9:3) while insisting salvation is only through Christ. Equality in Christ abolishes hierarchy in justification; it does not erase the categories Paul uses to explain God’s unfolding mercy.

Scripture is explicit that God shows no partiality; therefore no ethnic presumption, no moral impunity, and no dehumanization can be smuggled in under the banner of “prophecy.”

7) “Christ is the Seed and sole heir; Zionism offers inheritance without the Heir.”

Christ is the Heir. Salvation is only in Him. Amen.

But “Christ fulfills” is not the same as “Christ cancels.” If Christ’s heirship dissolves God’s covenant commitments, then Paul’s “until” logic becomes incoherent. Paul insists that Israel’s hardening is partial and temporary—“until the fullness of the Gentiles has come in”—and he grounds Israel’s future mercy in God’s faithfulness to the fathers and in the irrevocability of God’s calling.

See Romans 11:25–29 (BibleGateway, ESV).

8) “Romans 9–11 refutes Christian Zionism; it applies ‘at this present time,’ not two millennia later.”

Yochanan is right about one half of Romans 9–11: it destroys ethnic salvation and insists on faith in Messiah. But he misreads the passage by quoting “remnant now” as if it cancels “until then.” Romans 11 contains an “until.” You cannot call Romans 9–11 the refutation of any future mercy for Israel without deleting Paul’s hinge word.

9) “Israel was a temporary placeholder; now the people of God gather to Christ, not land.”

Yes: God’s people gather to Christ. But the New Testament does not treat the category of a future restoration of the kingdom to Israel as “propaganda.” After the resurrection, the apostles ask Jesus, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” Jesus does not rebuke the category; He redirects the timetable.

See Acts 1:6 (ESV).

Likewise, Jesus pronounces judgment on Jerusalem and then immediately adds an eschatological hinge: “you will not see Me again, until…” (Matt. 23:38–39). Judgment is real. The “until” is also real.

See Matthew 23:38–39 (BibleGateway, ESV).

Luke records Jesus’ statement that Jerusalem will be trampled by Gentiles “until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled” (Luke 21:24). The New Testament itself preserves future-directed “until” language.

10) “Replacement theology simply affirms fulfillment in Christ; Christian Zionism is not truly Christian because it places fulfillment outside Christ (2 Cor. 1:20).”

Every promise is “Yes” in Christ. But “Yes in Christ” can function as a guarantee or as a solvent.

In Paul’s hands it is a guarantee: Christ secures God’s promises so they cannot fail. In Yochanan’s system it becomes a solvent: promises are “fulfilled” by being redefined until their original contours disappear.

Romans 11 is the test: in the very chapter where Paul exalts mercy, he warns Gentiles against boasting over Israel and anchors Israel’s future mercy in God’s fidelity to the fathers. A guarantee exalts Christ as the faithful witness; a solvent turns Christ into a rhetorical tool for covenant amnesia.

11) “Jerusalem is ‘Spiritual Sodom and Egypt’; Jesus said ‘your house is left desolate’; God’s people were to flee and not look back—so Christians must not encourage Jews to return.”

Judgment texts are real. Cancellation is not the biblical inference. Revelation’s “Sodom and Egypt” imagery condemns spiritual corruption; it does not transfer deeds. And Jesus’ “desolate” pronouncement is immediately qualified by an “until” (Matt. 23:39). Emergency commands to flee in a moment of siege are mercy commands, not timeless bans on return.

12) “The West’s obsession with antisemitism is a political instrument—an alibi for imperial crimes.”

Moral language can be weaponized by power. Christians should resist propaganda—always. But it does not follow that antisemitism is imaginary. It is measurable harassment and violence directed at real neighbors.

The Anti-Defamation League’s Audit of Antisemitic Incidents 2024 reports 9,354 incidents and notes that, for the first time, a majority of incidents were linked to Israel or Zionism (58%). ADL’s Key Insights page provides the topline breakdown. And the U.S. Department of Justice summarizes the FBI’s hate crime statistics at DOJ Hate Crime Statistics.

These figures do not mean every criticism of Israeli policy is antisemitism. ADL explicitly distinguishes criticism from antisemitic elements. But they do mean this: geopolitical conflict increasingly spills into hatred of Jewish neighbors—in streets, on campuses, and online.

A present-tense reality worth naming (without baptizing any politics)

It is possible to refuse headline-driven prophecy games and still notice that history is moving in patterns the Torah and prophets taught us to recognize: scatter, preserve, regather.

At the end of 2025, Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics reported a population of 10.178 million, including 7.771 million “Jews and others.” See The Times of Israel (Dec. 31, 2025). The Jewish Agency’s figures summarized by The Times of Israel (Oct. 2, 2024) place the world Jewish population at 15.8 million with 7.3 million Jews residing in Israel. And even civilizational markers are striking: Encyclopedia Britannica notes that Hebrew was revived as a spoken language in the 19th and 20th centuries and is Israel’s official language.

None of this proves a prophecy chart. But it does make it harder to wave away the covenant question as purely theoretical—especially when Scripture’s covenant architecture and Paul’s “until” logic remain on the page.

Conclusion: Christ enthroned, covenants distinguished, ethics awake

If we keep the covenants distinct, keep Christ central, and keep Paul intact, Yochanan’s analysis collapses:

He treats Sinai’s conditionality as if it cancels Abraham’s oath—yet Genesis 15 depicts God binding Himself, and Paul forbids the annulment (Gal. 3:17).

He invokes Hebrews to erase Israel—yet Hebrews quotes Jeremiah’s New Covenant promise with Israel and Judah.

He treats “remnant now” as if it cancels “until then”—yet Romans 11 places “until” in the text.

He strings judgment texts into permanent abandonment—yet Jesus places an “until” on Jerusalem’s desolation.

So the dispensational claim, stated carefully, is not “Israel is righteous,” and it is not “politics is holy.” It is this: God’s covenant faithfulness can operate in stages—regathering, pressure, preservation, and then the Spirit’s work avoiding repentance—until Israel looks on the One they pierced and mourns, and the King is enthroned over all the earth.

That framework does not compete with Christ. It magnifies Him. Because it says the God who swore to Abraham is the God who sent His Son—and the same Christ who saves by grace will bring the story to its promised end.

Not yet. But not never.

Emir J. Phillips is a finance professor and writer with a longstanding interest in biblical theology and Israel in Scripture, with a focus on the prophetic storyline of the Old and New Testaments. His work aims to help evangelicals read contemporary events through careful exegesis—especially passages such as Deuteronomy 30, Ezekiel 36–37, Zechariah 12, and Romans 9–11.

You might also like to read this: