Earliest Hebrew alphabet found at Izbet Sartah reveals surprising Israelite literacy in the Iron Age

Part 3 of a three-part series examining the reliability of biblical scripture by exploring the archaeological site

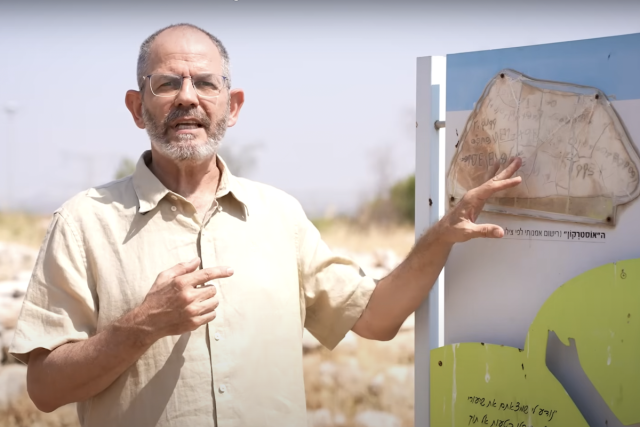

The period of Israelite settlement in Canaan, known as Iron Age I, is dated to the 12th to 10th centuries B.C. Very little written evidence has survived from this era. One particularly surprising find was uncovered as early as the 1970s at the site of Izbet Sartah, also known as the site of Eben-Ezer.

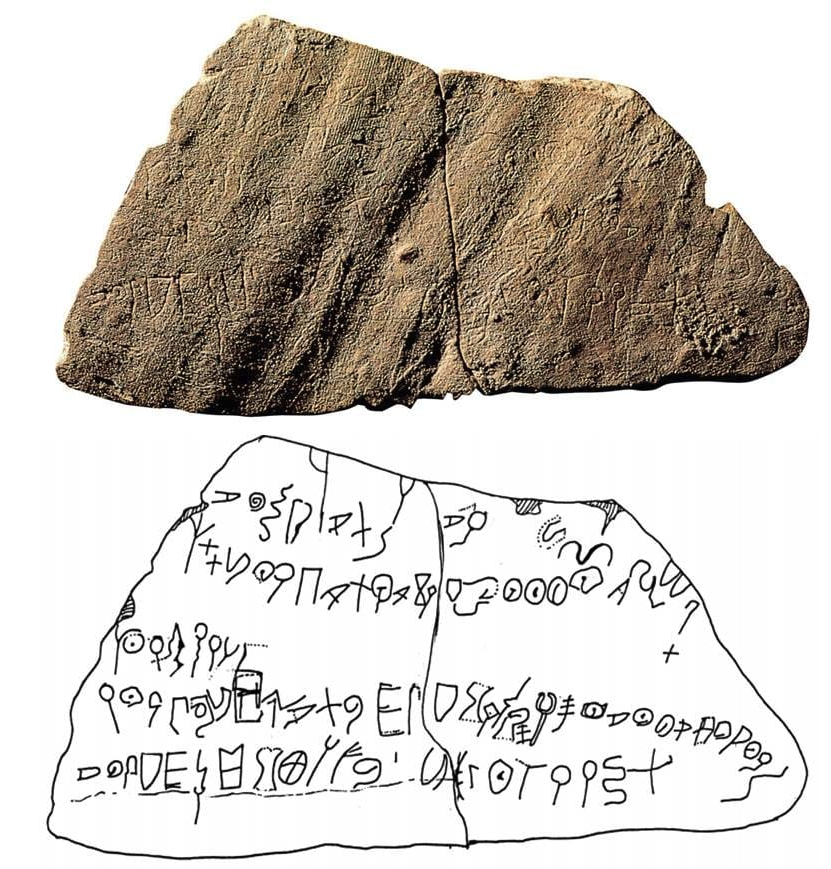

The discovery was an ostracon – a pottery shard inscribed with letters – containing what is likely the earliest inscription ever found at an Israelite site.

The site itself was a tiny village, home to, at most, a few dozen people for a brief period of about 200 years. The settlement was extremely modest in material terms: about a dozen simple houses of the “four-room house” type, characteristic of all Israelite villages during the settlement period, and a few small pits used as grain silos.

During excavations at the site between 1976 and 1978, one of the young volunteers found a pottery shard that, at first glance, looked no different from any other. However, he thought he saw something etched on it. He washed the shard and brought it to the heads of the excavation, and everyone was surprised to discover that it did indeed bear inscribed letters. Not just any letters, but letters of the proto-Canaanite alphabet, similar to other inscriptions found in Israel and the region, such as the Gezer Calendar. What does a written text at a small settlement site imply? It suggests an Israelite culture of literacy that surprises us. Later, more inscriptions were found, such as at Khirbet Qeiyafa. But that one dates to a later time, at the end of Iron Age I.

The proto-Canaanite alphabet had existed in the southern Levant for several centuries before the settlement period. In the early 20th century, Hilda and Flinders Petrie found an inscription in proto-Canaanite script at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, dating to the Middle Bronze Age, between the 16th and 18th centuries B.C. The inscription was discovered in a turquoise mine among Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions. This is probably the earliest alphabetic script ever discovered, indicating that the alphabet was likely invented in the area between Canaan and Egypt. The signs used as letters developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs, as seen in their strong resemblance to other Egyptian symbols. However, it is certainly an alphabetic script, with just over twenty different signs that repeat several times. Later proto-Canaanite inscriptions were found at Lachish, dating to the 13th century B.C.E. (Late Bronze Age), and in other places.

The script found at Izbet Sartah consists of more or less the same letters, but this is not a Canaanite Bronze Age site like Lachish or the turquoise mines in Sinai. Rather, it is an Iron Age I site identified as Israelite. Epigraphers believe that the Israelites, who migrated into Canaan from the east, adopted the Canaanite alphabet for use in their Hebrew language.

Linguistically, Hebrew is more similar to the languages of Transjordan (Moabite, Ammonite) than to Canaanite and Phoenician languages. Therefore, the use of proto-Canaanite letters in Hebrew does not mean that Canaanite languages were spoken, only that the same alphabet was used – just as the Latin alphabet is used for many different languages in Europe.

So, the question is: What is written on the shard?

Here, researchers faced a certain disappointment. The last line of the ostracon contains the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet written from left to right. Those are exactly the same 22 letters found in the Bible and in Modern Hebrew, only the font used is not the Hebrew we know today, but the proto-Canaanite script.

The other lines above contain several unsuccessful attempts to write the alphabet. Only the bottom line presents all the letters successfully. It may be a writing exercise – perhaps a child learning to write and practicing the letters he learned. There are no meaningful words on the ostracon.

Still, the Izbet Sartah inscription reveals several interesting facts. First, we see that the same letters we use in Hebrew today were already in use during the settlement period, that is, shortly after the conquest of Canaan led by Joshua son of Nun. The early Israelites used the exact same 22 letters we still use today.

Another interesting point: in two places, the sequence of letters is not the same as we use today. The letters Zayin (ז) and Chet (ח) appear in reverse order: first Chet, then Zayin. The letters Ayin (ע) and Pe (פ) are also reversed. One might think this was a careless student who did not learn the order well. However, such letter swapping appears elsewhere. The swapping of Zayin and Chet also appears in the Tel Zayit inscription, which is later and dated to the 10th century B.C. The Ayin and Pe swap is also known from other inscriptions at Kuntillet Ajrud in Sinai, which is even later, from the 9th or 8th centuries B.C.

However, the swapping of Ayin and Pe also appears, surprisingly, in the Bible! As is well known, some chapters in Psalms and Lamentations are acrostics, with each verse beginning with a successive letter of the alphabet. However, in some chapters, the letters Ayin and Pe are reversed – for example, the Book of Lamentations chapter 2 verses 16–17, chapter 3 verses 46–57, and chapter 4 verses 16–17. But chapter 1 presents the acrostic in the correct order we use now.

What does this mean? Apparently, there were several variations of the “correct” order of the letters, and this cultural heterogeneity is also seen in the Izbet Sartah ostracon.

If this were a writing exercise in this tiny village, then there were people learning to write, people teaching writing, and a culture of literacy in the early 12th century in a small Israelite settlement.

The Eben-Ezer inscription raises the possibility that the ancient Israelites wrote in Hebrew and that literacy was common in small villages, not just in big cities. Although very few similar finds have been made, this does not mean much. It is possible that writing was done on perishable materials like papyrus, and therefore, nothing has survived.

If writing – and even the study of writing – existed among the Israelites at such an early period of settlement, and even in a tiny village, what does this say about the literacy of the people during the period of wandering in the desert?

We know from the Bible that the people of Israel came from Egypt, where writing existed hundreds of years before. So, if the Israelites did write, would it be unreasonable to say that Moses could have written the Torah during the period of wandering in the wilderness?

The Izbet Sartah inscription, though modest in appearance, offers profound insight into early Israelite life and literacy. The text affirms the use of the Hebrew alphabet during the settlement period and raises important questions about the transmission of tradition, the development of written culture, and the plausibility of early biblical authorship. In this shard of pottery, we catch a rare glimpse of an educated people on the cusp of nationhood.

Click here to read Part One and Part Two of this three-part series on the reliability of scripture, where we explored the site of Ebenezer – its historical context and how its geography aligns with the biblical narrative.

Ran Silberman is a certified tour guide in Israel, with a background of many years in the Israeli Hi-Tech industry. He loves to guide visitors who believe in the God of Israel and want to follow His footsteps in the Land of the Bible. Ran also loves to teach about Israeli nature that is spoken of in the Bible.

You might also like to read this: