Gaza and the interim agreement: Israel’s legal right to bestow limited self-governance

The harrowing aftermath of October 7th has forced a necessary and painful re-examination of the foundational agreements that have shaped the Israeli Palestinian conflict for three decades. The pogrom unleashed by Hamas, an organization dedicated to Israel’s annihilation, was not an isolated event. It was the bloody culmination of a long pattern wherein Palestinian self-governance has been weaponized for jihadist war. This history demands a clear-eyed return to first principles: the legal architecture that grants Israel, as the sovereign power, the right and responsibility to administer the terms of Palestinian autonomy.

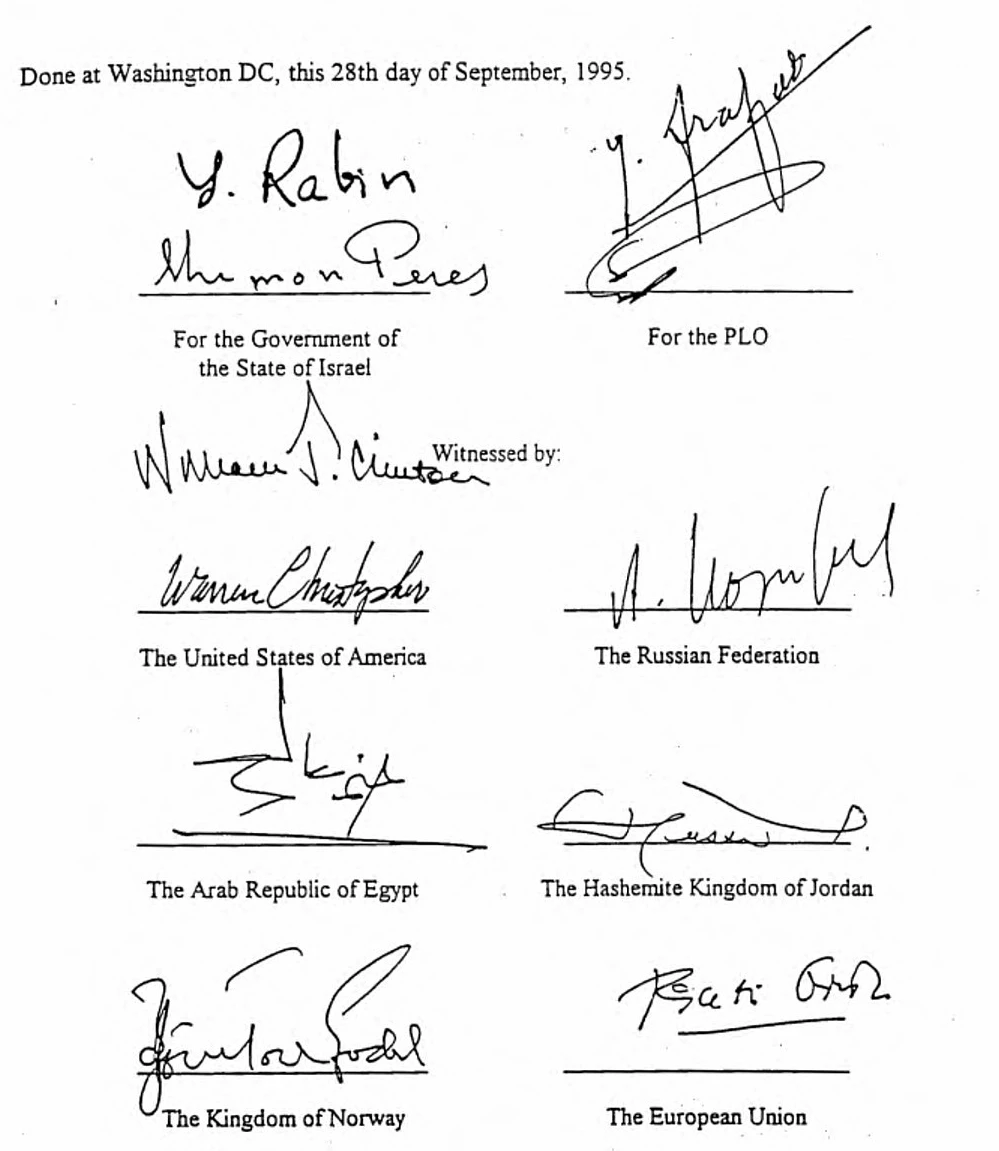

The legal framework for this authority is explicitly detailed in the Israeli Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—commonly known as Oslo II. Signed in Washington D.C. in 1995 and duly registered with the United Nations, this agreement remains the last, best negotiated instrument defining the relationship between the parties. Contrary to popular misconception, it did not grant Palestinian sovereignty or statehood. Its precise, legalistic language established a far more limited and conditional reality: the transfer of administrative authority from Israel’s military government to a newly created Palestinian Interim Self-Government Authority.

The key wording of Oslo II is deliberate and illuminating. Article I details the “transfer of authority… from the Israeli military government and its Civil Administration to the Palestinian Authority.” This was not a cession of territory but a delegation of certain civic functions. Article X stipulates a “withdrawal of Israeli military forces” from populated areas for redeployment to strategic locations, not a surrender of ultimate security control. Most critically, Article XIII reserves for Israel the overriding responsibility for “defense against external threats” and the “overall security of Israelis and Settlements.”

In essence, Oslo II created a model of limited Palestinian autonomy under ultimate Israeli security sovereignty. It was designed as a five-year interim process to build trust and institutions, culminating in negotiations for a final status agreement on borders, Jerusalem, and refugees. The Palestinian Authority (PA) was granted jurisdiction over civil matters like education and healthcare, and internal policing, while Israel retained control of borders, airspace, and all aspects of external security.

This legal structure affirms Israel’s standing right. As the sovereign state recognized by the United Nations—its legitimacy rooted in the League of Nations Mandate and confirmed by its admission to the UN in 1949—Israel possesses the legal authority to bestow and regulate the terms of limited self-governance to the Palestinian population within its territories. It is not an act of annexation; it is an exercise of the sovereign prerogative to administer disputed lands pending a final settlement, a practice common in international law.

The tragic history since 1995, however, is a story of this legal framework being violently violated by the Palestinian side. The agreement’s very foundation was the mutual renunciation of violence and a commitment to security cooperation. The letters of recognition exchanged were unequivocal: PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat committed to “renounce the use of terrorism and other acts of violence” and to discipline violators.

This commitment was shattered. The Second Intifada, a campaign of suicide bombings and shootings that murdered over 1,000 Israelis, was a direct and material breach of the Oslo accords. It demonstrated that elements within the Palestinian leadership, including factions of Arafat’s own Fatah party, chose jihad over state-building. The ultimate repudiation of Oslo came with Hamas’s violent takeover of Gaza in 2007. Hamas, an entity whose charter is a genocidal manifesto against Jews, and which explicitly rejects the entire Oslo framework, transformed the territory into a terrorist fortress. Every rocket launched from Gaza since has been a war crime and a violation of the interim agreement’s core principle.

October 7th was merely the largest and most savage manifestation of this rejectionism. It was not an act of national liberation, but a jihadist massacre designed to scuttle any possibility of peaceful coexistence. It proved conclusively that the current Palestinian leadership in Gaza—and significant elements in the West Bank—are not “peace-loving.”

This term is not rhetorical; it is a specific, legal requirement for statehood and United Nations membership under Article 4 of the UN Charter. A political entity that glorifies martyrs, invests its resources in terror tunnels and rockets, and whose stated goal is the destruction of a member state cannot, by any objective measure, be considered “peace-loving.” To advocate for the unilateral recognition of such an entity as a state is not a progressive act; it is a legal error that rewards violence and undermines the entire UN system.

Therefore, Israel is under no legal or moral obligation to proceed with a process that has been systematically abused. The unilateral offers of statehood made in 2000 and 2008 were met with violence, not negotiation. The unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 was met with war, not peace.

The path forward must be guided by the sober lessons of this failure. Israel must resume its role as the sovereign power responsible for security, as outlined in Oslo II. This means the current military operation in Gaza must continue until Hamas’s military and governing capabilities are completely dismantled. Thereafter, Israel must insist on a long-term security presence and overriding authority in the territory, facilitating the administration of civil affairs by a local Palestinian body that is devoid of Hamas and all other terrorist affiliations.

The fantasy of immediate, unconditional statehood must be abandoned. True self-determination for the Palestinian people can only be achieved after the total defeat of the jihadist ideology that has hijacked their leadership and betrayed their future. It must be conditional on a genuine, demonstrated, and permanent abandonment of belligerence.

Israel does not need to annex Gaza or the West Bank. It simply needs to exercise the rights it already possesses as a sovereign nation: to govern decisively within its borders and to bestow autonomy carefully, conditionally, and in a manner that guarantees the safety of its citizens. The Interim Agreement provides the legal basis for this approach. The charred homes of Kibbutz Be’eri and the violated bodies of young festivalgoers provide the moral imperative.

Aurthur is a technical journalist, SEO content writer, marketing strategist and freelance web developer. He holds a MBA from the University of Management and Technology in Arlington, VA.